Not every artist could so aptly compose a visual depiction of “negro sunshine” where blackness radiates light. Having accomplished that and more, Glenn Ligon gave patrons insight on his career thus far during Conversations with Contemporary artists at the High Museum on Jan. 10. The talk was a conversation, not a lecture, as Ligon walked listeners through a brief retrospective of his works that covered his more known pieces as well as the obscure ones. There were many moments of genuine laughter, not just from the subtle humor from the artist, but in the similarly understated humor of his artwork.

Ligon walked attendees through his works, like “Runaways,” a set of ten lithographs in the style of 19th century advertisements for the return of escaped slaves. His consistent method of appropriation in his art was as effective as it was amusing. In the case of “Runaways,” the artist’s friends described him, and Ligon used the quotes to compose the lithograph; a practice which resulted in advertisements that said,“Ran away, a man named Glenn. He talks sort-of out of the side of his mouth, and looks at you sideways,” and “He’s socially very adept, yet, paradoxically, he’s somewhat of a loner.”

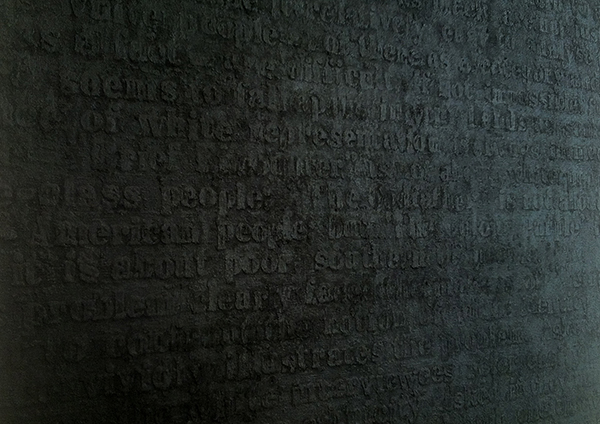

At another point, he expounded on his movement from monochrome back to color and appropriated quotes from the equally colorful humor of Richard Pryor. Glenn Ligon made a comment on Pryor’s humor which could be paraphrased to apply to his own: though much of the work is certainly hilarious, at the same time it also is not funny at all. On the surface, the phrase “negro sunshine” seems a comical oxymoron, but it is also the essence of pride and strength in the outlook of many in the Black community. To the casual viewer, his stencil works, which progress from clarity to muddled intelligibility might seem easily dismissed with little more than a smirk but there’s a gravity in the way a message sounds so profound initially but becomes garbled through repetition. Phrases such as “Black is beautiful” or “Black and proud” come to mind.

Glenn Ligon’s work, though an intertextuality of the words of others, seems to be such an open and vulnerable look at the artist himself. While that can be debated, his open candor with the audience was not particularly debatable. His honesty was genuine throughout. In some cases, the matter were small such as his description of how bad he felt his early works were. In other instances, such as how many artists write about themselves early in their careers because no one else will write about them, the matters were large. The latter served as a moment to teach: when artists write about themselves, they can set the tone of the conversation on their work.

One guest asked if he ever appropriated his own words. Ligon’s response was that he felt the words of others were far more interesting. Perhaps in years to come, Ligon’s intellectual musings might be the ones used to make art in the way he uses James Baldwin’s words.