While driving through the town center, Lao Duan, a Chinese man who lives in Shanghai, found his face displayed on eye-catching electronic billboards by the side of the road. The text of the billboards read, “this man is untrustworthy,” displayed along with his name and ID number. Beside the public denunciation, Lao also found his bank account and credit card frozen.

The story started when Lao couldn’t pay back his loan, which he took out to purchase coal for his business. As he told NPR, because of a change in China’s energy policies, the coal market collapsed and subsequently, Lao’s purchases became worthless. Upon knowing Lao’s inability to pay his loan on time, the government put Lao on a blacklist in its social credit system. After a few visits to the town center, Lao also found the faces of his co-workers, those who couldn’t pay back their loans as well, displayed on the billboards as well.

In China, the fictional, personal rating technology in “Nosedive,” an episode from the “British TV anthology “Black Mirror,” is a reality. It’s called the social credit system, a rating system the Chinese communist government introduced in 2014. The system rates companies and individuals based on their behaviors, with credits that would result in rewards and punishments. Like the characters in “Nosedive,” each person has a credit score rated based on their behaviors at work, the public sphere, and their online activities. The scores accumulate into letter grades, with A, representing exemplary behaviors, C as a warning level, and D as a grade that would pin you to a blacklist. Those with high credit scores would enjoy benefits and rewards, such as express security screening in the airport, higher scores on dating websites, free cable TV, job promotion and easier house buying. Those with a low score would be blacklisted and receive punishments, such as being barred from public transportation, their children blocked from entering elite schools, blocked access to social services, slower internet service, and ineligibility for jobs. The system deducts score from people who are close to those with low credit scores, which supposedly encourage each person to regulate their behaviors.

The government is preparing to implement the centralized system countrywide and cover its 1.42 billion citizens by 2020. Last year, the National People’s Congress reappointed Xi Jinping as president, with no limits on the number of terms he could serve. Xi would oversee the implementation of the social credit program. According to the Wall Street Journal, the system collects big data, ranging from an individual’s internet social interactions, online shopping habits, money management (such as loan repayment and paying bills), to volunteer activities, and adherence to traffic laws and family-planning limits. The system deducts points from individuals for “bad” behaviors. For example, points off for buying too many video games (which the government deemed as indulgence), crossing the street on a red light (violation of law), having more than two children (exceeding the legal limit) and inability to pay off debt on time. “Good” behaviors, such as donating to charity, visiting parents (supposedly implying filial piety) or buying diapers for children (which supposedly suggest care for family) would score more points.

China utilizes advanced technology to collect big data — such as using facial recognition, businesses

In an NPR interview, 32-year-old IT engineer Xu Ranjan said the system made his city Rongcheng, especially in terms of traffic, better. He said, “in the past, if you’re a driver and you’re not giving way to the pedestrian, probably you won’t feel that you are doing something wrong.” But with the social credit system and street cameras, drivers would behave because of the weighty consequences. “I think in the history of human being developing towards, like, communities if everybody can follow the rule, I’m sure it’s very good for, you know, every individual living in the city,” he said.

In 2017, Chinese journalist Liu Hu found himself barred from taking the train. Radio Free Asia reported that Liu discovered he was blacklisted because he hadn’t officially apologized to a person who sued him for copyright infringement. Desperate, he published an apology in the newspaper, but the regional court wasn’t satisfied and kept him on the blacklist. What could satisfy them? Liu didn’t know, because after contacting legal departments across the country, nobody could tell him why his apology wasn’t enough.

According to the Chinese government, they designed the system to promote sincerity, trust, ethical behavior and security in the country. Over the past few decades, China has a long track record of corruption, business cheating

Another of its implication is not only the system’s limit of personal freedom, but how the government would use it to crush those who disagree with the Communist party doctrines. The country is already notorious for jailing and killing (masked as staged suicides) dissidents, including political activist Li Wangyang, who was killed in 2012 after jailed for 22 years for taking part in the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. This system would discourage and alienate people from raising concerns about the government’s legitimacy.

Perhaps the system is yet to be installed on a national scale yet, but as surreal and dystopian as it is, evidence of its existence certainly exists. Last year, freelance journalist James O’Malley posted a video taken inside a bullet train. On the video, a female voice announced in English

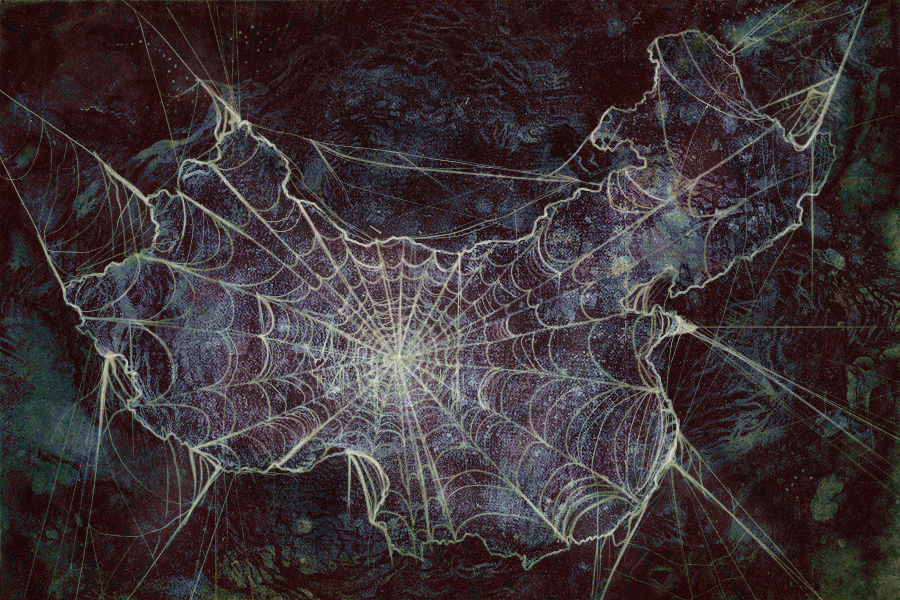

Though we have yet to know the system’s scale and pervasiveness in the future, what is certain for now is that somewhere in this world, a technology from “Black Mirror” is no longer fictional but a reality. Kat Ash, graduate illustration student, illustrated this dystopia in her drawing for this article: those who live in China must navigate in a dark web — and try not to get caught.

Big data is rating you; Big Brother is watching you.