On Oct. 10, the Swedish Academy announced the winners of the Nobel Prizes in Literature for 2018 (postponed last year due to a sexual assault scandal) and 2019: Olga Tokarczuk and Peter Handke. Immediately after the announcement, heated controversies flared, the fiercest of which centered on Handke, who is a known defender of genocidal Serbian dictator Slobodan Milošević, and who has loudly expressed doubts of the Bosnian Genocide’s authenticity.

In response to the backlash, Mats Malm, a member of the Swedish Academy, made a comment: “It is not in the Academy’s mandate to balance literary quality against political considerations.”

This is not the first time politics has come into play at the Nobel Prizes, nor is it the first time artistic prizing has been politicized. For example, last year’s Grammy Awards telecast was famously anti-Trump, featuring a comedy segment of celebrities and Hillary Clinton reading from “Fire and Fury” by Michael Wolff. The response was divided — while some supported the Grammy stance, some felt like art should be enjoyed without politics getting involved.

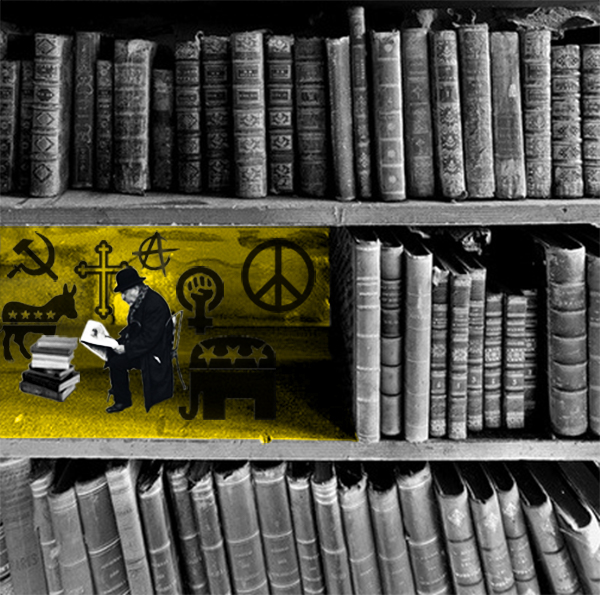

But, should it really? Can art even be apolitical? Can anything, at that, be apolitical? What is politics, after all? In these modern days and age, we are too consumed by politicians espousing ideologies that we automatically think of politics as Red, Blue, Green, etc. But really, at its core, politics is about power. And as long as humans are to live in any kind of civilization, there is always going to be someone in power, and the influence of their decisions is always going to affect, in varying degrees, the reality of the rest. Nobody is untouched by politics, and consequently, whether they like it or not, nobody is apolitical.

And art, at the end of the day, is the expression of how humans perceive their reality. So where, as the title of this article asks, does art meet politics? The answer: everywhere.

“Art is inherently political in that it absorbs and reflects the culture in which it is produced,” said Paige Gray, a writing professor at SCAD. “And every culture has these ideas and these imbalances of power. […] They’re all very different levels of consciousness. For example, someone’s going to write a song telling a story of what it was like to grow up in South Side Chicago. Art can help reflect and tell some kind of story about that moment in time, and that moment is always going to have the residue of the politics at that time.”

While people like Malm might believe that artistic merits and political consciousness are two separate things, the history of cultivation of artistic styles tells a different story. For example, take a landscape painting, something that seemingly offers no statement. Is it painted in the style of the Impressionist? The Expressionists? The Cubists? Each and every artistic movement has always been anchored to the politics of its time; revolutionary art starts from revolutionary thoughts, and revolutionary thoughts are simply radical political opinions. Art is created upon intents, and intents are always political.

“Take a look at Modernism in the 1920s: there was an ambiance, a feeling following World War I that infused people’s ideas. It might not have been conscious, it might not have been in the choice of subject, but it was in how the subject was projected,” said Gray.

Separating art and politics, therefore, is a pointless task. Separating art and politics in the case of Handke, Nobel laureate, is a foolish attempt, considering how Handke is a very political individual who produces very political works. His literary skills were learned and honed within this political mindset and his books are soaked in opinions. So while the Swedish Academy did not claim its stance on Handke’s opinions, by granting him the highest honor of literature they are giving him a platform to further spread his ideas, which in itself is a political act.

This conclusion may come as very bad news to some people, who find themselves caught in a world where politics is getting noisier and noisier by the hour and where everyone is political and very loudly so.

“I hate to say it, but people now, they have their views they want feel comforted with their views,” said Tom Lea, Vice President of Newsgathering at the Weather Channel. “They seek out people with the same opinion and they may not even get past the first paragraph because they don’t like the premise.”

Just because all art have some level of politics doesn’t mean that we should only explore works whose ideas are similar to our own. Quarantining ourselves from political discomfort means quarantining ourselves from great art and provoking ideas, which can only results in a stubborn and myopic mindset.

So what to do for the politically anxious art enthusiasts?

Embrace all art to our heart’s content, sure, but always we should be aware of what these artworks stand for. Choose to acknowledge the politics of the work to our comfort, yes, but never should we kid ourselves that our refusal to consider the artwork’s political implication means that the politics is not there.

And if things ever seem too complicated or confusing to navigate, well, that’s still no reason to worry. Complicatedness and confusion are only signs of intellectual and moral evolution.