When you think of Atlanta, skyscrapers and traffic are probably the first images to come to mind. The dazzling lights radiate the sky, and the sunny weather keeps pedestrians warm, perhaps too warm, as they bustle down the sidewalks. Everybody has something going on, so it’s easy to miss news about climate and racial justice when there’s always another tragedy in the news cycle. However, these issues creep up whether you’re watching or not.

What is Cop City?

In September, the Atlanta City Council voted to allocate 85 acres of land to build a massive police training complex, costing taxpayers $30 million while the other $60 million comes from corporate donors. Governor Brian Kemp released a statement supporting the vote, saying,

“Our capital city and surrounding metropolitan area are facing a crime crisis. That’s why I have dedicated additional state resources, including the Department of Public Safety’s Crime Suppression Unit and millions of emergency dollars in state funding, to support the Atlanta Police Department. This has been a productive partnership and their joint efforts are seeing significant progress with dozens of wanted criminals taken off the streets, hundreds of stolen vehicles recovered and thousands of arrests and citations for unlawful conduct.”

To reduce crime and strengthen the Atlanta Police Department, the facility will allow law enforcement to act out emergency scenarios, providing:

- Offices for police leadership and veteran training

- Events amphitheater

- Emergency vehicle operations course

- Mock city for real-world training

- Farmland

The Atlanta Police Foundation calls this project a “Public Safety First Campaign,” but locals call it “Cop City.”

Lay of the Land

Pre-1911: A family of plantation owners, the Keys, profit from slave labor on stolen Muskogee (Creek) land.

1911-1922: The City of Atlanta buys this land from the Key family and creates the “Honor Farm” for prisoners to perform farming labor.

1922-1980s: Multiple investigations delve into the Honor Farm’s abuses, including but not limited to racist human rights abuses, hazardous working conditions and dumping untreated waste into Intrenchment Creek.

1990s: The farm closes, and afterward becomes a hidden attraction for urbex enthusiasts and graffiti artists.

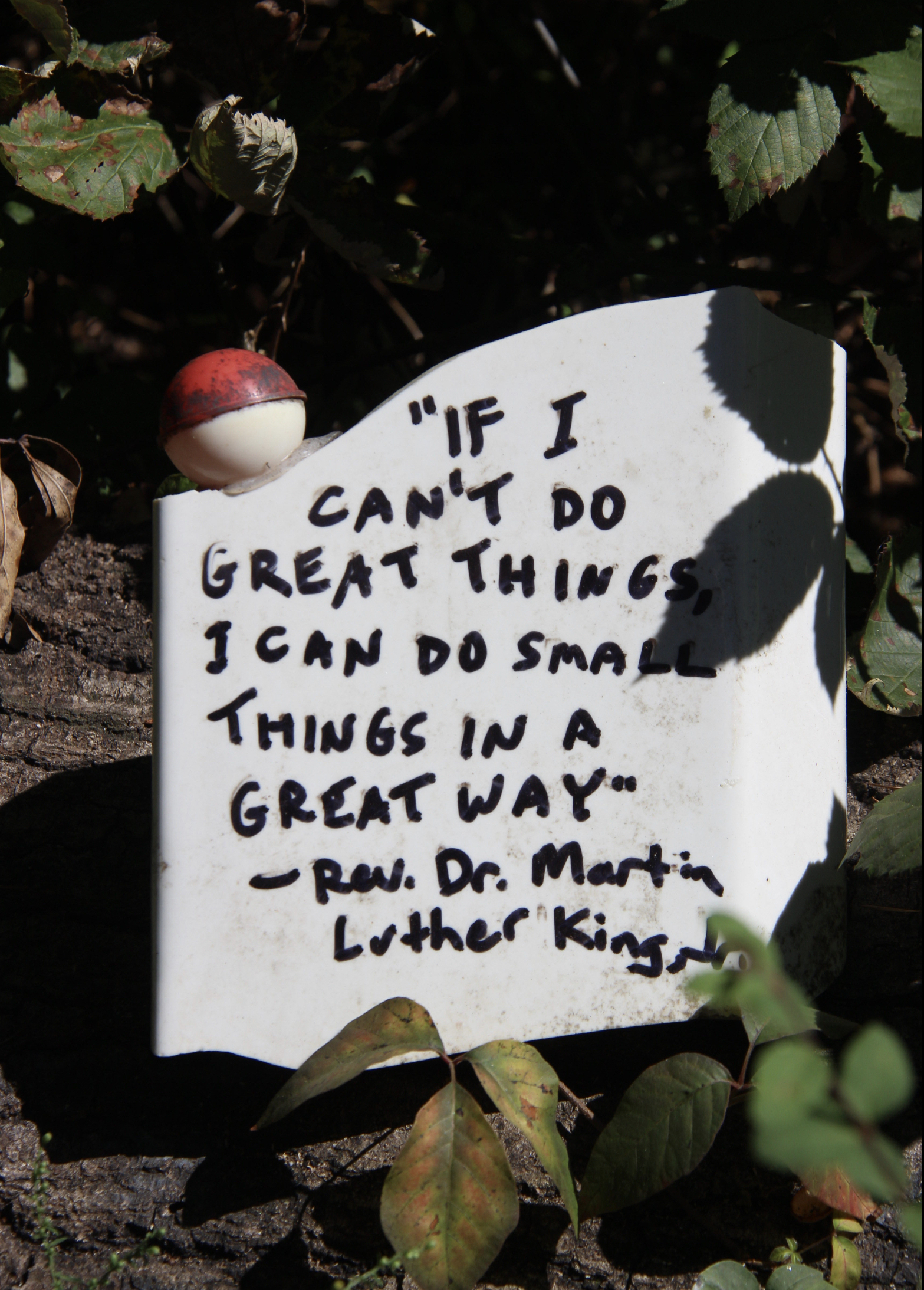

Today, DeKalb County’s South River area is a staple hiking area for locals, secluded on the outskirts of small-town Georgia. Deer and squirrels roam the dense woodlands. Cranes and turtles cool off in Constitution Lake. Hikers from across the country trek with their kids and dogs in tow. Artists turn trash into treasure at the Doll’s Head trail, making it a bizarre monument to environmental preservation. So, how did people react when they found out their forest was going to be scrapped for Cop City?

Photo courtesy of Jackson Williams.

An Uphill Battle

“It’s clearly not for us, it’s not for our community and it’s going to be adverse to us and our people,” Kwame Olufemi of Community Movement Builders said in an interview with 11Alive.

The Atlanta-Metro area is home to several historically Black and Indigenous communities that fear systemic racism will flourish under an increased police presence. The facility’s noise and light pollution will disturb homes and schools, encroaching on family-centered spaces that are already surrounded by a youth detention center and state prison. Doctors from Emory urge the city to reconsider its decision and divest the money to public health initiatives. Construction would also influence South Atlanta’s topsoil degradation and flooding, which would worsen South River’s status as one of America’s most endangered rivers. Thousands of grassroots activists and community organizers have answered the call to action — some climbing the trees themselves to protest deforestation and state violence. Despite overwhelming pushback, Cop City is under construction, but that doesn’t mean opponents are going down without a fight. It’s only the beginning.

“We don’t want to live in a police state. We don’t want to live in a world that’s ravaged by climate change. And, you know, we just want to protect the nature that exists. And for me… this whole thing is coming from a place of love”https://t.co/tzo4TY9HJx

— Defend the Atlanta Forest (@defendATLforest) June 16, 2022