Writer’s Corner: “Goodbye Daddy” by Hiu Ching Cheung

The Writer’s Corner features poetry, essays, short stories, satire and various fiction and non-fiction from SCAD Atlanta students. To submit your own work for the Writer’s Corner, email features@scadconnector.com.

“Goodbye Daddy” by Hiu Ching Cheung

Trigger Warning: Suicide.

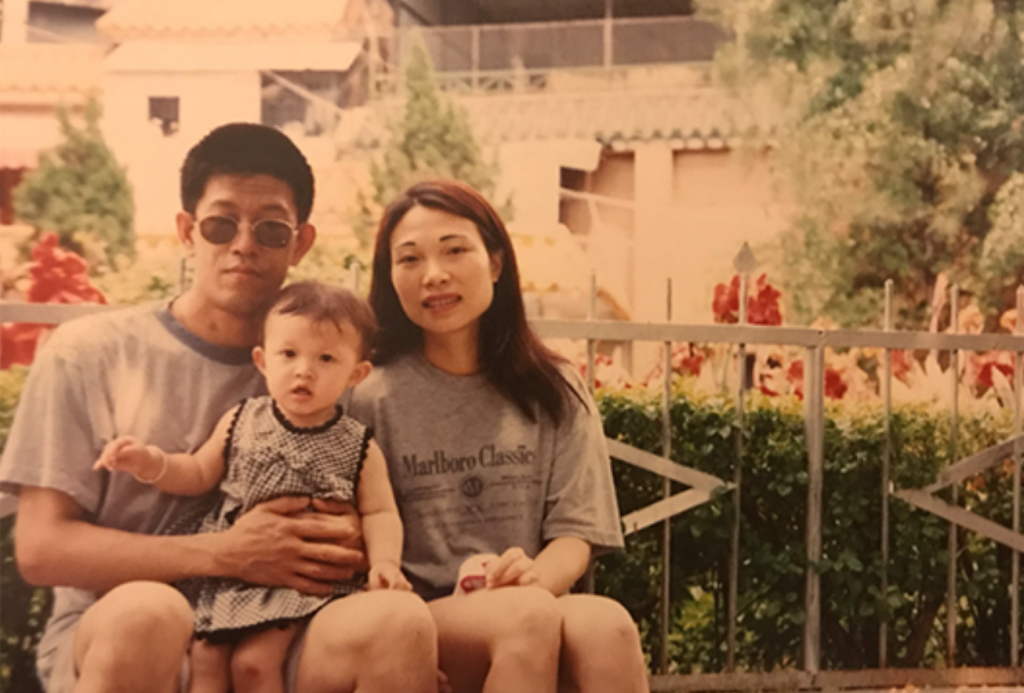

A family photo on Ching’s desk from 1997:

The young woman is Jenny Ho, and her husband was William Cheung. They both looked too young to be parents in 1997. William held his little girl Ching with his rough hands, as she sat on his lap. William loved Ching so much, but he never called her name. He called her “daughter’ because he was her only father. The weather was hot, and it was a one-take film photograph.

After nineteen years, it became yellowed. William died of a heart attack.

Ching received six missed calls when she was volunteering for a drama show in which she would never succeed. She picked up the phone call during her break time. It was late, around nine o’clock. Too late. It was an unfamiliar number from a man who called himself the police.

“He was unstable,” the police said.

No matter how many times Ching tried to clarify the definition of the word — unstable — the police kept repeating the same sentence. Ching was nineteen, and she wanted to be a great actress. It was a dramatic moment in her life, and it was the first time she could drop her tears without any extra help. The tears were salty and uncontrollable. They reminded her of the soups her father promised to cook for her. He knew how to control the amount of salt, and his soup was always well balanced between bitter and sweet. He had promised her the soup that very morning.

“Will you come back home for dinner tonight?” William asked Ching.

“No, Dad. I have rehearsal.”

It was the last sentence Ching said to William. Ching rushed to the elevator, and William went back home when he finished his shift. Ching forgot whether she said a proper goodbye to her dad or not, but she remembered her lines. The rehearsal lasted for a day because the director, Mr. Yun, was unsatisfied. He never permitted actors to leave the rehearsal early, but he allowed Ching to go with three hundred dollars.

The other actors gave Ching money for the taxi so that she could travel from Tsuen Wan to Tuen Mun. Ching was the only nineteen-year-old in the troupe, but her role was an older countryside girl. She didn’t know she was bad at acting, and she looked too young for her character. The road to the hospital was short, and she didn’t have much time to grow up.

Ching’s sobs were louder than the radio. The night was frozen, and the host of the radio show was telling jokes about dead people. She cried with all her heart. It was the first time she took a taxi by herself. The driver was a similar age as her father, and his voice was deep. Ching didn’t look at his name card next to his plate, but she knew he was already driving as fast as he could. It was a rainy day, and the water pelted the window. Ching’s face stuck to the window, even though she felt cold and solid. She wanted to sense the rhythm of the rain because it made it seem like the taxi was driving slowly. She knew William’s heart had stopped a few times, and she needed to rush to the hospital.

“Just let it go.”

It was the only sentence the driver said to Ching. She wanted him to keep speaking to her, but he stayed silent. The rain was heavy until she reached the second door of the hospital. Then it stopped.

She got out of the taxi.

It was a sunny day. William was still sitting there. The photographic paper had great quality, and it would last a long time. Ching was still a little girl, and she looked innocent like usual. It was a forgettable day, but they must have eaten breakfast or lunch before they came to the little garden. William always wore glasses because he couldn’t see when he took them off. Ching was young and the glasses were thick. She always noticed her father’s glasses, but she forgot to look at his hair. His hair was black, and it didn’t look like her baby brown hair. She didn’t know one day her father’s hair would become white and he would leave without a proper goodbye.

When Ching got into the emergency department, Jenny was there without her boyfriend. It was a normal day, but the sterilized water must have passed the expiration date. It stunk. Jenny gave a hug to Ching, and she allowed her tears to show. Ching didn’t hug Jenny back, because it would be unnecessary. Ching didn’t expect Jenny to be there, but the police found her number in William’s phone — ‘Wife.’ Jenny called her boyfriend and said they were waiting for the doctor, and Ching pretend she didn’t hear anything. She looked around the emergency department, and everything was white. The place was pure — we were born with nothing, and we leave with nothing.

The doctor called Ching and Jenny to the fourth floor, where they had transferred William to ICU. It was the best thing they could do, but his heart didn’t follow the electricity from the machine. Jenny and Ching sat down on chairs, and they jumped up every time the doctor came out for the latest update. The doctor came out three times and told them to prepare themselves. Jenny kept saying they should grab some clothes for William, so he would have clothes when he recovered from the hospital. The air conditioner kept running and Ching was shaking under her jacket. She didn’t tell Jenny how cold she was. She thought William must be colder, and she wanted to feel her father — one last time.

“We are so sorry. We have tried our best.”

Jenny and William always wanted to be good parents. They both wore gray shirts, and Jenny put a gray checkered dress on her daughter. They made themselves look like a family in the photo. Jenny sat closer to William, but she didn’t touch her husband or her daughter. William didn’t smile, but Jenny smiled for him. They were close, but there was a gap between them. It was a small gap, but Ching blocked it in front of the camera.

The doctor gave William’s clothes and pants back to Ching and Jenny. Ching received them and they were cut into two pieces. Jenny said the doctor cut William’s clothes and pants because they needed to put the machine on his chest. It was an emergency. Everything had been cut in two — they would never be whole again. Ching hadn’t seen Jenny for a while. Since they signed the papers, Ching always wanted to stay with William. When she stayed with Jenny, sometimes her boyfriend visited them and made her feel unsettled.

A year before William died, they got divorced. It wasn’t because of the boyfriend, but a big gap in their relationship. William never told Jenny about his problems, even though he owed a big debt to the banks. He never let Jenny in on his problems because he was a man. He never told his daughter about this because she was too young. They always had conflicts about money, life, and their daughter. They argued. Then, they always kept silent for a long while. Ching thought of herself as an owl, but she didn’t have a pair of wings. She was stuck in the nest for so many years.

Ching believed her mother was the one to blame because Jenny always talked about money. She didn’t tell Ching about the woman on her father’s phone, and she didn’t tell her that William was the one who sent the divorce papers. Jenny didn’t want to destroy Ching’s image of William as her father, so she destroyed her image as a good mother. She allowed Ching to punish her. She thought her death would make Jenny upset, but it was out of her control.

Ching attempted suicide four times.

Ching raised her right hand in the photo, like she wanted to say something. But she didn’t know how to say a word yet. Jenny was a good mother, and she couldn’t stop worrying about her daughter’s life. Jenny loved writing, but she didn’t have money to study, and she knew she needed to take care of her family. She wrote good articles, and sometimes she wished she could rewrite her life.

Ching wrote her last letter to Jenny, and she wore her white dress to the bridge. She looked down at the vehicles passing by underneath. They were fast. But she told herself — it would be quick. She had so much to ask her father. She thought about her life on the bridge for three hours, to prepare herself for death. But when she tried to step off, she was always reminded of God. It was hard to explain to people, but a voice stopped her to kill herself. It was her God whom she believed since she was a child. This voice disturbed her and made her look upon the sky. The sky was blue. So blue. Ching learned about this God in her high school, and people said only his death could give us hope. She thought about her death; if she died, she would make the death of her God meaningless. She knew God loved her, her mother loved her and somebody she didn’t know loved her. It was hard, but she stepped back.

After Ching failed to kill herself each of the four times, she stopped for a while. But she needed to smell the aroma of William’s expired shampoo on his bed. The bed was cold, but she warmed it with her soft body. She just wanted to sink, so she might find her father in the deep of the mattress.

She kept sinking on the bed until she was twenty-six.

Ching didn’t cry in the photo, even though she was only a baby. William and Jenny were still there for Ching, and they had just started their marriage. They would have each other for many years, but not forever. It was the beginning of Ching’s life.

After Ching stopped trying to kill herself, she started to write. She believed it was a secret gift that God put into her heart for a while, but she didn’t notice when she kept trying to focus on her loss. In one of her writing classes, she was thinking about how to rewrite her family’s stories. It wasn’t an easy class, but Ching was trying to leave William’s bed after eight years. She got up a little bit and sank her fingers into the keyboard. She told her classmates she might cry when she wrote about her father.

“Is okay, we have tissues,” her classmate Noel Sabiñano said. Ching heard Noel, but she didn’t reply to him. He was gentle and kind. Maybe he would never remember what he said — like the people who gave Ching tissues at the funeral. It had been eight years, and Ching had forgotten whether she used tissue for her tears or not. She didn’t know why she forgot she cried at William’s funeral. Ching made the same mistake every time she wrote about her father. She wrote how still she was at the funeral, but it was a lie.

She thought rewriting her memories would make her feel better, but it became worse. William was fading in the story. She forgot it wasn’t a fiction class but nonfiction — she couldn’t lie about anything. She wanted to lie about her tears because they couldn’t explain the woman on his phone. She wanted to lie about the tears because they couldn’t explain the debt in his bank account. She wanted to lie about her tears because she was older now. She needed the answer before she could convince herself — William was gone.

“Cry, Ching!” a crazy twenty-six-year-old woman shouted to the photo. “I said cry it out loud! Tell your father how painful it is. Tell your father you tried to kill yourself four times when you didn’t know how to react to his death. Tell your father you wanted to know about the debt and his new woman. Tell your father you wouldn’t accept his death until he answered all your questions. Tell your father you would carry his death through your whole life as a debt. Tell him! Tell him! Tell him!“

Ching was still a little child in the photo, and she didn’t look at her father. Little Ching looked at the woman from the frame, expecting she would explain everything to her. But the woman stopped, she recognized it was too much for little Ching. Too much. She knew little Ching should be a child of William, and she didn’t need an answer to forgive William. The woman wanted an answer to paying her debt, a debt of her sadness, but it was too much for little Ching. The woman decided to carry her debt to God; if God wanted her to be a writer, then she shouldn’t be a debtor. She told little Ching that their debt had been canceled, and they had been healed. She forgave her father. She sank her finger into the keyboard again and wrote the ending of her father’s nonfiction.

Goodbye Daddy.