Takato Yamato: The father of Heisei Estheticism

Takato Yamato is one of the most brilliant painters to debut during the turn of the century. His style so eloquently suggests both an ageless traditional quality and a then-contemporary approach to its subject matter. Yamato’s signature style, Heisei Estheticism, is calm in its darkness.

It finds a way to depict the grotesque and horrific through a filter of beauty and decadence. While at the same time calling back to the Neoclassical era of Poussin, as well as traditional Japanese scroll paintings. There’s a transcontinental stir that creates the exact blend that makes his works so creative. A blend that both pulls from Asia’s neighboring continent and expands what was thought to be there.

Japanese art after Hiroshima

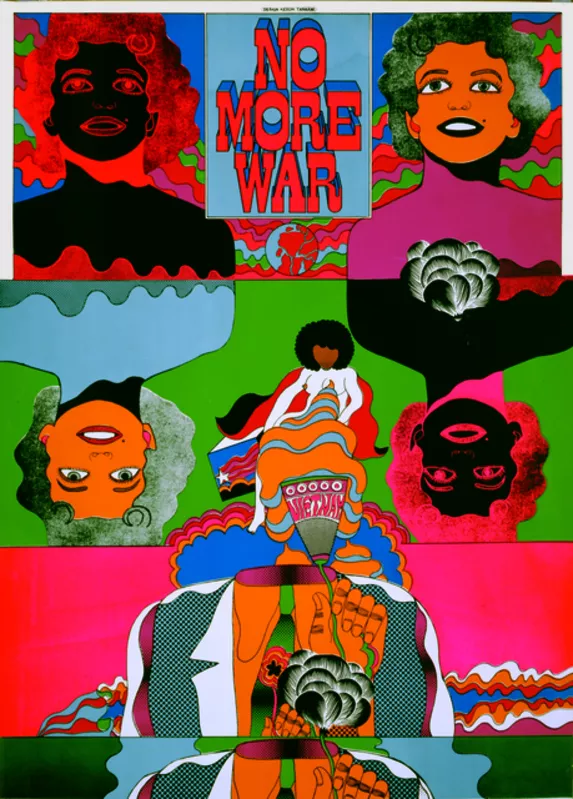

Yamato was born into 1960s Japan, placing him only a decade and a half away from the bombing of Hiroshima. Hiroshima naturally disrupted a lot of things, but it affected art in some very distinct ways. For one, it blew the lid off of Japan’s exclusive qualities. This was not the first time Japan had experienced an era of cultural exchange with outside artist. In those cases, however, it was usually a few wealthy travelers jet sailing to Asia and coming back with a newfound wonder for their neighbors to the East.

Due to war, however, people of many different economic backgrounds were exposed to Japan, and vice versa. Widening the gap of how much influence could go back and forth. Secondly, art after Hiroshima had a sense of longing. A lot of styles were emerging during this time, but the consistent through-line was the appropriation of styles popular in America or Europe, as a way to express Asian trauma.

Intro to Neoclassicalism

And Yamato was no different. His work has a clear and deliberate call to Neoclassicism. Neoclassicism is an art movement defined by its participants’ awe toward the art of the Renaissance. And in turn, Yamato had the same revolve for the style, but also aimed to spin its tenants on its head.

A lot of Neoclassicists believed their style was the best because it was modest, simple and clear. Yamato utilizes the same level of clarity, rendering his figures with the same attention to anatomy and precession, but forgoes modesty and simplicity to create extremely busy compositions. This in turn communicates a world of beautiful models being devoured by death and destructions.

Take Yamato’s “Suffering,” for example. Anyone who knows their art history can immediately tell that the figure to the right is meant to be St. Sebastian, an early Christian martyr believed to have survived being tied to a tree and shot by arrows due to the grace of God, and as such became a popular subject of 17th century art. But where this subject is usually depicted amongst an evenly clear background, and embedded in the glorious lights of Heaven, Yamato’s St. Sebastian is in a wasteland. The background is shrouded in an illegible smog. The tree that he’s tied to looks more like bones. The pain the arrows are causing him is more explicit. And to his side is a towering pillar filled with symbols of lust, death, freedom and captivity. A confusing mess staring directly at St. Sebastian, and he not able to look elsewhere.

Another interesting artifact of Yamato’s work is the sexual component. He tended to tantalize the idea of sensuality in a way that was explicit in its metaphors but disturbing it its portrayal. Take his famous mirror vampire portraits. Whether the subject is male or female, it’s unclear if they are biting a same sex lover or a clone of themselves. Either way, the sexual undertones are impossible to ignore.

Yamato also loved memento moris. A visible signifier of death, usually a skull, that was meant to remind the viewers that death was inevitable and thus they should always live a God-fearing life. But in Yamato’s hands it feels more like an omen of death. Almost like the personal fingerprint of the grim reaper lurking over his subjects’ heads. In some cases, even nuzzling up their necks.

As a man of few words, it’s not clear what brought Yamato to his distinct style. Perhaps it was the years of distress and death that plagued his country during his childhood and directly before it. Or perhaps it was seeing the same people who planted the seed of that distress, now intruding onto his country again for money. No matter the reason, his gripping blend of Ukiyo-e and Neoclassicalism will forever be engrained in the epitaph of Japanese artistry, truly making him the father of Heisei Estheticism.