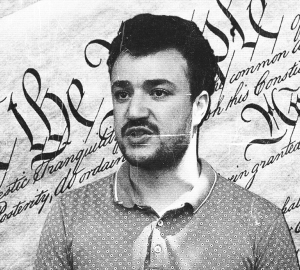

Twenty-eight-year-old Toronto native, Mustafa, spends the 40-minute course of his 12-song album singing street folklore. Mustafa the Poet has been working within the industry since as early as 2016. In 2021 he released his first solo project “When Smoke Rises” garnering a large dedicated following. He’s been co-signed by Toronto music superpowers such as Drake and Sampha and on September 27th, 2024, he released his actual debut album Dunya.

Mustafa has been notably vocal about how black men and their music are perceived. From his early works with his collective “Halal Gang”, he has been a vocal supporter of black culture and music, and equally vocal about his want to not be confined within societal views. His sonic approach is much more akin to folk music, even working with a collaborator of Taylor Swift’s Folklore. He sings and delivers tales unique to the Western black experience (especially those of low-income inner city environments) yet in a medium commonly dominated by white audiences and creatives. Through his relatable tales, yet generally Eurocentric music medium, he allows black people, namely the black youth, to see and hear themselves in a piece of music we standardly do not.

The Sudanese-Canadian Muslim begins his album by asking what you would do in the “Name of God”? The first lines within this beginning track tell a story many are likely familiar with, “both our eyes are red, but you’re high and I’m crying.” The song seems to ring the tale of someone wanting to “get better” for the sake of someone. The sentiment is not lost through his usage of first-person pronouns, the listener could be the high person or the crier. Mustafa does this consistently throughout the album allowing the listener to truly embody all sides of whatever story is being told. He states that “every letter of fire you read me when I’m tired, is replaying as a choir.” In the Islamic faith, music being halal or haram is commonly a point of contention. The line shows an immense amount of duality; representing letters and words as something that can burn and be ingrained, though delivered through something as holy as a choir. The chorus closes by asking “And when you left me waiting, I thought, did you do it in the name of god?” Mustafa’s forgiveness is a major speaking point in this album, he always finds himself able to forgive those who left him hurt the most, allowing himself to perceive this pain as something bestowed upon him by Allah.

The next song is what solidifies Mustafa as a black man breaking boundaries. Reminiscing on his brother who was shot and killed, Mustafa opens the track with his angelic voice asking “What happened my nigga?” When I had first heard this line, surrounded by other black men, we instantaneously replayed the song. The sentiment is so uniquely black that the room I was in was immediately impacted with four words. Reflecting on his upbringing and the differences between his reaction to his environment and his brothers, “And I was right where you are, but this hood tore us apart I don’t blame you for losing your heart.” It’s very clear and it’s very blunt, similar to the impact of simply asking “What happened?” Understanding what low-income inner city environments can breed, Mustafa does not fault his brothers, his “niggas”, for losing themselves and in turn their lives, he forgives them.

Mustafa’s want for the youth to see themselves in his music is likely why he writes allowing for such open interpretation. Within the track Imaan, through stanzas of pain, Musafa cries upon what can only be perceived as a forbidden love. “Imaan” the word means faith and can also serve as a name. Mustafa speaks to faith itself and a person with a namesake. This duality makes the song’s impact more universal. Mustafa’s “wearing the things” Imaan has said, “on his face like they’re a prayer.” The namesake allows the line to exasperate exactly how important Imaan’s words are to Mustafa as a person and to his faith. Intertwined with strings not commonly found in Western music, this song paints an image of a love that is not standard or normalized within Mustafas’ world. He states that Imaan and his family would “never find their way to the same living room.” Mustafa understands the generational disconnect between their families and the world Imaan and Mustafa traverse through. Before the chorus begins Mustafa pleads, “I know that you can’t hold me, but just hold me, like you want me, like you got me.” These lines seem very likely queer coded which would assist the idea of a forbidden love, yet even if they aren’t, the understanding is still the same and universal.

Mustafa the Poet is not always crying a sad tune. SNL or “street nigga lullaby” is what would happen if trap music and folk fused. The song contains vocal samples and spoken word from Atlanta rapper J.I.D. The music video shows Mustafa donning a bulletproof vest surrounded by his friends within his old hood. The video is presented in a way many black people are familiar with in an almost stereotypical rapper fashion. It makes the song more impactful and much more likely to resonate with the black audience that does not see themselves in this music. He is still reflecting on loss, society, faith, and a multitude of other important concepts similar to how rappers do, but delivers it through standardly non-black music in one of the blackest music video formats possible. Truly expresses genius in his songwriting and the hilarious duality of a “street nigga lullaby.”

Mustafa speaks directly to God on “I’ll Go Anywhere.” Mustafa will go “back home” even though he “hates” it. He may even go to Mecca as is expected of all Muslims who are able-bodied and able to afford the pilgrimage. He reflects on his elders and may even go back to “where father got his rage from,” he will do all this and then move to bring god closer to him and vice versa. Even through his questioning of Allah’s ways and the questioning of his plan; mentioning his aunt who committed suicide. Despite all the negatives of the places he will travel and the painful confusing losses he faces, his faith remains strong and Mustafa will continue growing closer to god.

Track nine, “Gaza is Calling”, is a tale of longing for home. Mustafa calls for a person to “go north” regardless of their lack of “willpower.” When speaking to this Gazan person he knows war weighs heavy on their heart and their faith, he knows this person wants to “find the people who want to kill you.” As a Muslim, he draws a parallel to the life-or-death gang environment and the war currently being fought. He knows firsthand how dark that want can go, and reinforcing the theme of the heart, he states: “There’s a place in your heart that I can’t get into.” Each time the chorus is sung, “Gaza is calling” it then ends with “There’s a wall that’s in the way.” Until the final uttering where he makes sure listeners understand why Gaza is calling and why this person is not responding or going. Because every time Gaza says this person’s name, “There’s a war that’s in the way.”

Daniel Caesar, another Toronto native, joins Mustafa for a duet on “Leaving Toronto”. Continuing on his journey of pain Mustafa dedicates this song to one of the major catalysts of it. Continuing to weave street life with folk music the song starts with a sample of someone rapping “Drop a bag on the kid, Drop a bag on the glock, Heart boy but I don’t heart a lot.”

Mustafa is leaving because Toronto has “nothing left to give him” and in turn has taken so much from him. His pain and disdain are clear, stating that he would drive “five hours to cry in Montreal.” He is leaving the “things he’s said” the “last of his friends” but he knows he will come back. He will come back “running to the past” but he will not get stuck in it. Mustafa will continue running “till I pass through you (Toronto).” While he may be leaving Toronto and the pain it may breed, he loves and forgives those there. He repeats the line twice at the end of the song “If they ever kill me, make sure my killer has money for a lawyer.” Forgiveness is paramount to Mustafa even through his disdain.

The album ends with Nouri, Arabic for “my light.” Mustafa loses himself when he “thinks about you (Nouri) passing.” He is calling to another friend and begs for them to come back knowing they are gone. Loss seems to be the one consistent in Mustafa’s life, especially in this album. In this letter to Nouri, he even tells them of their mother’s pain and confusion “Where have you gone… why have you gone away?” Their mourning is clear: “Any room you’re in is where God is remembered. Any door you open the angels will enter.” The songs end with 3 repetitions of “Did you leave her back there? Did you leave your dreams there?” It is a rhetorical question, he knows Nouri has unfinished love to give and aspirations, but all he is left to do is wonder.

Mustafa’s debut album is not a one-off event it is an establishment of expertise. Mustafa’s poetic ability knows no bounds, especially not those of musical expectations. His want to encapsulate the black youth in the music they are not represented in, intertwined with his identity as a Muslim creates music for the scrutinized to find solace. He understands what is wrong with this world and through his faith and his music does what he can to help align Dunya.