Defending digital photography

An analysis of the differences between digital and film photography

By Russell Cambron

While the vast majority photography done today is done digitally, many photographers hold fast to film photography. Sometimes, this is done for personal or artistic reasons. Film is what you’re used to. It’s what you love. It’s your “process.” But some go farther than this. Some claim that film photography is inherently, objectively superior to digital photography. These photographers want to treat their subjective, personal preferences as objective fact. In their view, you aren’t a real photographer unless you shoot film.

Some subjective preferences for film have an objective basis. For example, one of the most common arguments for valuing film over digital is that one prefers the look of film. If we understand how a photograph is made from film versus how a photograph is made digitally, then we understand that there is indeed an objective, material basis for this claim.

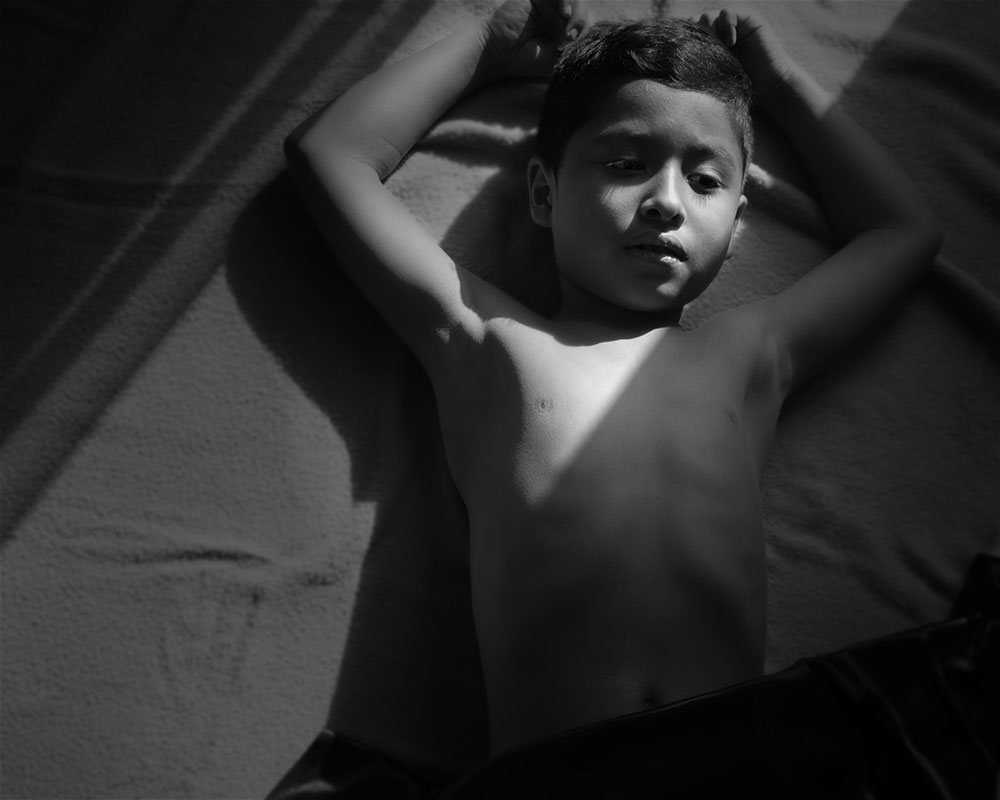

A film photograph is produced by two chemical stages of exposing light-sensitive silver to light. First, in the camera, the shutter opens to expose light-sensitive silver halide crystals on the film to light. These crystals gather where there is more light, leaving the spaces of lower light. When developed in total darkness, this film yields a negative image called, appropriately enough, a negative. Second, light is passed through the negative onto light-sensitive photographic paper that is also coated with light-sensitive silver crystals. These crystals gather at areas of light and leave areas of lower light dark. Thus, a positive image is produced. Because of the organic shapes of the crystals on both the paper and film, one could call a film photograph a kind of chemical collage.

Digital photography, on the other hand, is, well, digital. In place of silver halide crystals on a role of film, light is recorded on a digital sensor within the camera. This digital sensor is made up of picture cells, or pixels, that record the information entering the camera. This information is digitally stored on a memory card inside the camera and then uploaded to a computer. A positive image can be viewed immediately upon uploading the image or on the LCD screen on the back of a digital camera. This means that, unlike film photography, digital photography does not necessitate printing.

If you decide to print a digital image, you must use a printer of some kind. To make a professional-grade picture, you must use an inkjet printer. The information from the image file is translated by the computer and the printer to tell the printer what colors and tones of ink to “jet” onto the paper (hence, “inkjet” print.)

The resulting print is called an archival pigment print and could be compared to a very precise, computerized painting. But then, could we not also call this printing process a kind of precise, digital collage? A precise pointillism? In any case, we see that there are in fact objective, material differences between digital photography and film. How significant these differences are, objectively speaking, remains unclear.

In most cases, these objective differences are literally microscopic. There are some exceptions. Printing an unusually large print can show these differences. Photographs shot in low light situations will show what is called “grain.” In film photography, larger grains of silver halide crystals are required to make the film more sensitive to light and thus more amenable to shooting in lower light situations. In digital photography, multiple pixels work together as one larger pixel in order to make the digital sensor more sensitive to light. In either case, the individual points that make up the photograph become more visible. Today, however, digital photography has evolved to the point where even these differences are minimal. Thus, preferences for digital or film photography remain subjective, even in low light situations.

Another argument from the “film-is-objectively-superior” side addresses process rather than aesthetic. Proponents of film photography argue the benefit of shooting film is that it slows you down, forcing photographers to stop and think about the picture we are composing. Film makes us stop and think longer and harder about the composition and lighting before snapping the shutter because we have fewer chances to get it right.

Again, there are objective truths to this argument. Large format photographers—the old-school photographers you see covered under dark cloths taking pictures with a large camera with bellows—get only two shots before they must reload their film. Medium format and 35mm photographers get however many shots are on a given roll of film—12, 24 or 36 exposures. While digital photographers may get thousands of exposures from the same shoot without ever having to stop to load a new memory card into the camera, a film photographer will never get more than 36 exposures without having to stop to reload their camera with film.

Is having a limited number of chances necessarily a good thing? It’s true that we can learn from limitations, but they can also have a negative impact. They can make us miss opportunities, and they can be needlessly frustrating. Why force someone to miss a shot just because they don’t have enough film? Why force one to have to go through hours of developing film when they could simply upload their pictures to a computer in minutes or even seconds?

The limitations of film could force someone to be more frugal with their picture taking, but one too many missed opportunities or frustrations could also lead someone to hate photography. It could lead someone to drop photography altogether before ever having a chance at becoming a serious photographer—all because one person or another told them that they weren’t a real photographer unless they used film.

Moreover, the prejudice that digital photography breeds unthinking photographers (and unthinking photography) relies upon a caricature of digital photographers as the only ones who buy a camera and just start snapping pictures without any attention to detail, without ever learning how to improve our photography. In reality, until digital photography came along, the vast majority of camera buyers did exactly that. They went out and bought a film camera and some generic 400 ISO film (good for most lighting situations) and started snapping pictures. Only a few took the time to learn more and to slow down and compose better pictures. Even fewer learned how to develop their own film and print their own pictures.

Personally, I love film photography. I own a large format 4×5 camera, a medium format twin-lens reflex camera, and several 35mm cameras. I love cranking the levers to advance the film one exposure forward. I love developing the film and going into the darkroom to see the image “magically” appear before me in the developer. Even though I know it’s really a chemical reaction that makes the image literally come together as grains of silver clump together on the photo paper, the process still feels pretty magical to me.

I also love shooting digitally. Having information travel through all this hardware and software in a camera and computer to a printer may not sound as poetic as grains of silver on film, but the fact that humans have been able to come up with all this technology is still pretty magical to me. I am just as much in awe of digital technology as I am of the fact that humans once learned how to harness light in a dark box called a camera obscura, then simply a camera and then learned how to use chemical processes to print that image onto metal, glass or paper.

Though objective differences between digital and film photography do exist, I do not believe that film photography holds a monopoly on forcing photographers to slow down and take better pictures. Digital photography also forces you to slow down and consider composition, lighting, printing and everything in between. This is not because of the hardware or the technology. It is because good photography requires all of these things, regardless of whether it is film or digital photography.

Ultimately, a real photographer is one who takes her or his work seriously, regardless of whether she or he works digitally or with film. Yes, film photography requires you to be serious if it’s done well. So does digital photography.

As with any art form, you have to be serious. You have to take your time. You have to spend hours upon hours practicing and perfecting your craft. You have to stick with it from start to finish, and you have to love it. Art is about doing what you love. No one should be made to feel inferior just because the medium they love to work with is different from what someone else loves.