“Ready Player One,” a film adaptation of a novel by Ernest Cline, was directed by Steven Spielberg and recently released in theaters. Reactions to this film, particularly on the internet, were mixed. Both the film and the novel use ’80s pop cultural references as the central focus of the plot in a way that causes many critics to call “Ready Player One” fan fiction as an insult.

“Ready Player One” is the exact opposite of fan fiction.

Fandom today can be broken down into two categories — transformative and curatorial. Transformative fandom creates new work based on the source material fan fiction, fan art, fan videos and edits. Curatorial fandom is based on knowledge. On making sure all of the pieces of the original work are in order, knowing all of the trivia and how all of the minor details work. “Ready Player One” is the apex of curatorial fandom.

Neither Cline nor Speilberg use the characters or the stories to create something new. A character reenacts a movie he likes word-for-word getting bonus points for accurate delivery as part of the quest but doesn’t change that movie or engage with it in any meaningful way. No one spends time thinking about why a movie or game did this or that, because the only thing that matters in the “Ready Player One” universe is knowing everything.

In one of the chapters of “Ready Player One,” two of the characters argue over whether or not the film “Ladyhawke” is canon, or relevant to their central quest. A member of transformative fandom would look at that argument and ask, who cares?

Fan fiction specifically is an example of transformative work that takes an existing piece and uses the established characters, setting or storyline in a new and different way. This is not a new practice. “Paradise Lost” is Bible fan fiction, and “The Aeneid” is fan fiction of “The Odyssey.” And yet, when fan fiction is mentioned in casual conversation, most people who don’t spend time on certain websites think of “Fifty Shades of Gray” and “My Immortal.”

It’s derided by published authors as something lesser, as something by and for emotional and obsessive teenage girls, full of poor spelling, obnoxious self-insert protagonists and stilted prose. Lonely Christopher recently published a rewrite of Stephen King’s “The Shining” that he then tried to pass off as beyond fan fiction, even though taking an existing work and transforming it is the definition of fan fiction.

There is no barrier of entry to putting your fan fiction online. Anyone can make an account on fanfiction.net, on Wattpad, or on Archive Of Our Own, (AO3). And because there is no barrier, no base standard of quality required to upload a work, the quality varies from professional to an 11-year-old on their first computer. This is how “My Immortal” came to exist. It’s also how many writers currently making a living off publishing original novels got their start, bolstered by comments and likes and hits on these websites.

In “Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide,” media scholar Henry Jenkins wrote, “Fandom, after all, is born of a balance between fascination and frustration: if media content didn’t fascinate us, there would be no desire to engage with it; but if it didn’t frustrate us on some level, there would be no drive to rewrite or remake it.” Transformative fandom tends to be composed of people that feel underrepresented by the media they consume.

According to Tumblr user Centrumlumina’s 2013 AO3 demographics survey of more than ten thousand users, only 38 percent of the userbase of AO3 identifies as heterosexual, and only 4 percent identifies as male. AO3 is maintained by the Organization for Transformative Works, a volunteer organization sustained by donations. The OTW also publishes a quarterly journal containing academic analyses of transformative work and fandom, maintains the Fanlore Wiki, and supports a legal defense fund to protect the rights of fan creators. The idea for the AO3 came about as a reaction to the commercial startup FanLib’s desire to profit off fan creators, when popular Harry Potter fan fiction writer Astolat proposed a fan-controlled archive with, “no advertisements, no restrictions on content, and a commitment to fic as fair use.”

Fan fiction is written by people who watch a show or a movie, or read a book, and look at what they are given and think, but what if this happened?

Fan fiction today tends to focus on the characters’ inner lives and emotions to a degree not often found in original work, which is why some people stop reading original work once they discover fan fiction. There are plot-heavy action stories out there, but even a political intrigue drama will have more focus on character development than the typical published fiction of the same type of genre.

Nobody reads a “Fake Relationship Alternate Universe” (AU) story for the plot but for the characters. Every character has a different reason for getting into a fake relationship and ways of dealing with the situation once it happens. The ability to keep a character consistent over dozens of alternate universes, in dozens of interpretations, is an ability unique to fandom. It can take a fictional Japanese high school volleyball player and cast him as an entomology professor, a time traveler, a demon king, a witch, and if the fiction is written well, he will always feel like the same character.

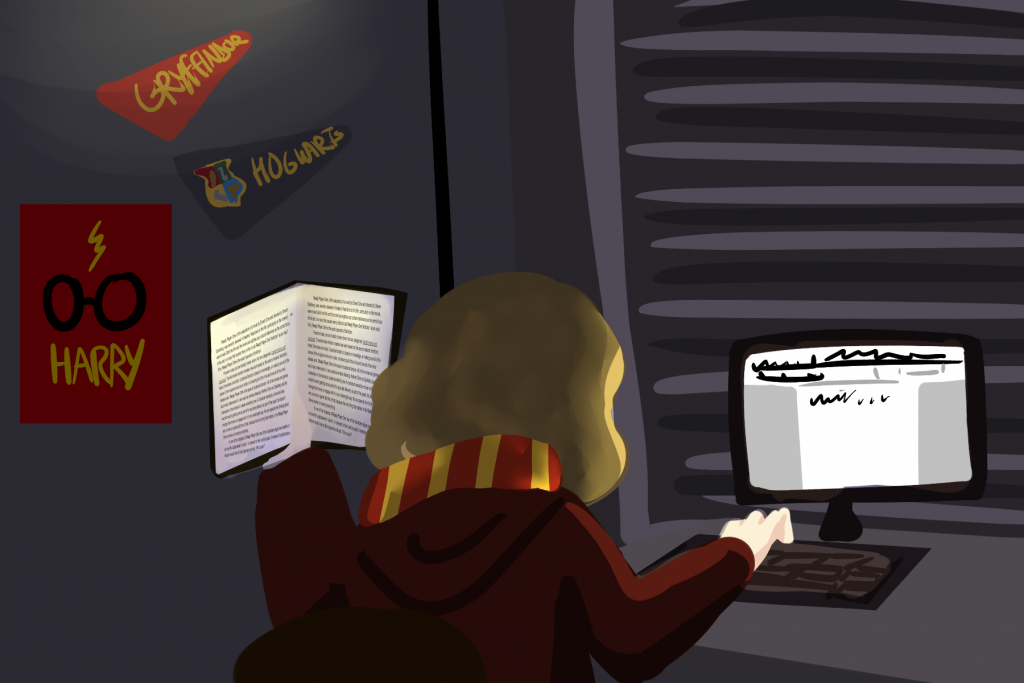

I discovered fan fiction on the Scholastic kids forum for Harry Potter fans when I was about 10 years old, and it was like getting struck by lighting. The realization that I could make up what happens after the epilogue and nobody could tell me no, made my childhood self feel superhuman. Writing fan fiction for me is now an exercise in writing comedy, characterization, pacing and telling a complete story in a short amount of words. It’s also fun to come up with alternate universe scenarios that combine elements of everything I love into one thing — and to pretend these characters I admire are like me.

While people post fan fiction on forums and fandom-specific web archives, fanfiction.net and AO3 are the most widely used archives today. Both websites allow users to search by fandom, though AO3 has a more detailed tagging system than fanfiction.net. Both allow users to bookmark, subscribe to, comment and publish their own work.

Fan fiction isn’t inherently written badly. It’s not inherently weaker than a work that’s been published. It’s an expression of caring enough about something that you want to leave your mark on and make it yours.