One morning, Gregor Samsa woke up from troubled dreams to find himself transformed into a monstrous vermin. A slight inconvenience, it seemed.

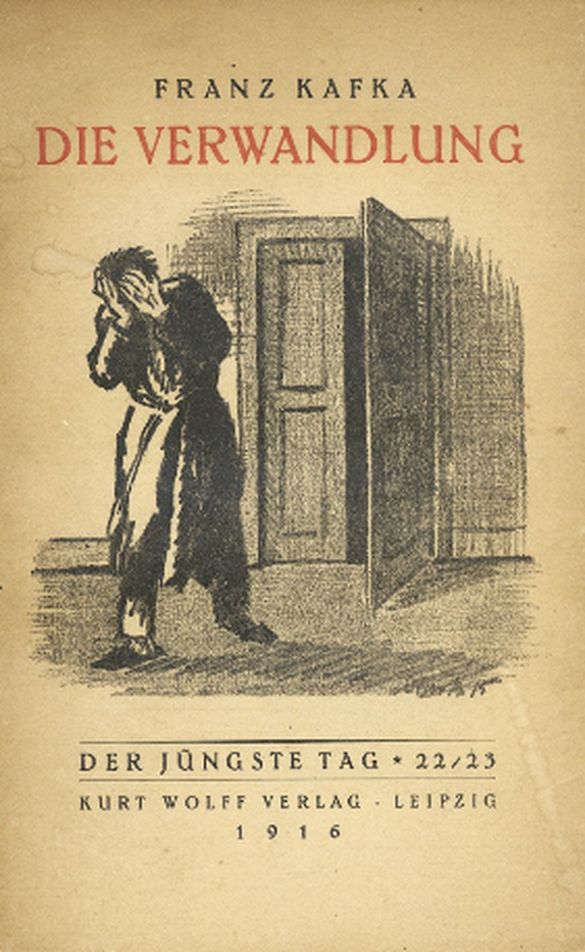

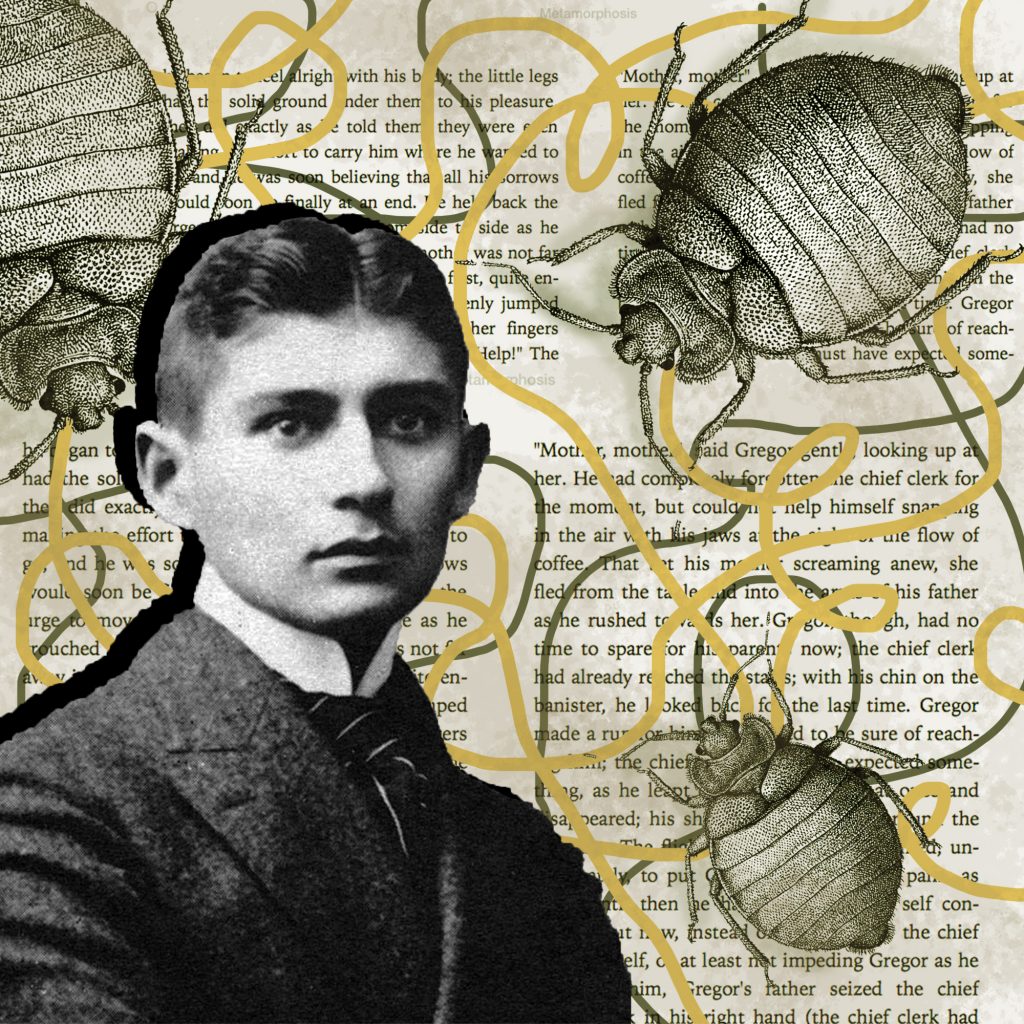

Many literary critics, avid readers, and A.P. Literature teachers have argued that Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” was all a big metaphor for mental illness. After accepting that he was a giant bug, Gregor proceeded to barricade himself in his room as his voice, thoughts, and actions became increasingly insect-like, which, to us in the non-shapeshiftable world, represents his loss of identity and his de-scent into insanity. Gregor, the sole breadwinner of the house, could win bread no more – the task was transferred to his narcissistic parents and loving sister, all of whom later came to resent him. He was neither useful nor lovable to them now that he was a bug or a disabled, anorexic, and potentially psychotic mess of an ex-commerce traveler.

Unlike most of his fellow humans, Gregor the Commerce Traveler did not care for music. But Gregor the Bug did. Music attracted him; it captivated him and moved him and drew him out of his dark animal den and back into the human’s room. Could this mean that Gregor the Bug was, in a way, more human than Gregor the Commerce Traveler? Could Gregor the Insane be more human than Gregor the Sane?

But just what exactly does being “human” actually mean? To Gregor’s mother and father, it meant being able to work, to elicit an income, to provide for the family. Gregor’s money marked his grati-tude to his dear old parents, and without it, he was an ungrateful burden to be dealt with. Working was the essence of his existence. It also happens to be the essence of a machine. Gregor the Human was no human, not at all. He was a robot, an assembly of parts and pieces designed to carry out its masters’ wishes. His human thoughts were programmed, and his human actions hardwired. But as Gregor’s mental capabilities was shredded, his machine ran out of fuel and his gears fell away, re-vealing behind them a giant bed bug – a creature of unresolved inferiority complexes, guilt, and self-hatred.

There’s this thing that I like to call “The Onion Theory,” a term I derived from the movie Shrek. The quote of its origin goes as follows:

“For your information, there’s a lot more to ogres than people think. […] Ogres are like onions. […] Onions have layers.”

There certainly is a lot of truth here. “There’s a lot more to ogres than people think.” There’s a lot more to people than people think. We, like the foul-breathed, green-skinned, hot-tempered cartoon creature, are like onions, with layers and layers sheltering our inner selves. The closer those layers are to the surface, the darker the color is, so as to blend in with the earth, so as to assimilate into our surroundings, so as to be accepted and valued, hiding away our cores like it was something horrible and rotten, not knowing that other onions walking and talking out there also bear a similar core. Our layers help us survive in the pragmatic world and help us function smoothly, like Gregor the Machine, and as time passes by we come to define our mechanic actions as normal. It is only when we can no longer hold up these shields of normality when our heads spin and our hands shake and our knees buckle that these layers shed, suddenly and all at once, exposing to the world just what we really are.

And what are we? What is a human at his core? For most, right there next to our hearts’ desires, it’s a bundle of secret fears and insecurities, always so successfully suppressed but has now come out. The pure energy of released chaos wrecks his already-damaged mind even further, trampling away all his confidence and assurances like demons with hooves. But our inner selves are not hoofed demons – life is not one of those angsty teen-fictions. No, our inner selves are simple creatures, the result of our most honest and deepest thoughts, the essence of who we are. These creatures can either tame us or be tamed by us. For those of us who fall slave to them, we become them. Like poor Gregor Samsa, we become a mess of fear and distrust and self-hatred, lacking sensible and coherent thoughts, not unlike a sacred animal. Like poor Franz Kafka, who struggled with severe depression his entire career, we let these emotions flow out of us and into the work we do. Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis,” as much as it is an illustration of depression and anxiety, is in itself a result of depression and anxiety. Through this embodiment of Kafka’s misery, we see what he was made of genius mixed with self-hatred and guilt perpetuated by a cruel father. The product of an agonized human is the window through which we discover who they, and we, truly are.

Another example of the Onion Theory is Spanish painter Francisco Goya. As a royal painter, he produced paintings according to his clients’ requests — portraits and illustration of kings and dukes. As an artist, however, Goya was obsessed with the theme of violence, many of his pictures depicting a scene of bloodshed never before seen on canvas. There was a darkness that surrounded his art, that differentiated him from other painters. For example his nude women, unlike the radiant, curvaceous shapes favored by contemporary art, were never smiling, never glowing with youth and beauty, but were old and wicked and, above all, realistic. It can be said that Goya was haunted by reality, by the cruel ugliness of it, so much so that it eventually consumed him. In 1819, Goya bought a villa close to Madrid, and at the same time he was seriously ill. On the walls of his new home, Goya painted a series of fourteen paintings that were later known as the Black Paintings,3 all of which were bleak nature scenes or grotesque, menacing figures in acts of vileness or violence. These pictures were never meant to be seen – they had simply been an outlet; borders of a larger skull in which Goya’s thoughts flowed; where, free of the shapes of emperors and queens, he confessed his fears of going insane and his bleak views on the fate of humanity. The horrendous “Saturn Devouring His Son” was among these Black Paintings, and it happened to be one of Goya’s most famous works.

But this is not one of those arguments that celebrate depression and anxiety. It does not advocate for the public peeling of onions or for the thought that everybody needs to walk around with their guts spilled out for the whole world to see. No, this is a statement of acceptance: I hereby accept the fact that sometimes losing one’s mind is a way, an ugly way, to find one’s heart. Most of us onions are chaotic at the core, and our implemented social perception of weakness had taught us to fear this chaos, to deny audience with the creatures inside, to shy away from what we really are. So we call shrinks frauds, meditation mumbo jumbo, and honest conversations pretentious nonsense. And then we implode, and the creatures, angry from entrapment, go on a rampage. But as I have said before, these creatures can either tame us or be tamed by us, and if we have enough strength and courage and “how does that make you feel’s,” we can control the madness and make peace with it. To successfully come back from mental illness means to regain control of one’s brain and seize control of one’s heart; to walk around as a fully-layered onion, but one with a core that is, finally, at peace.