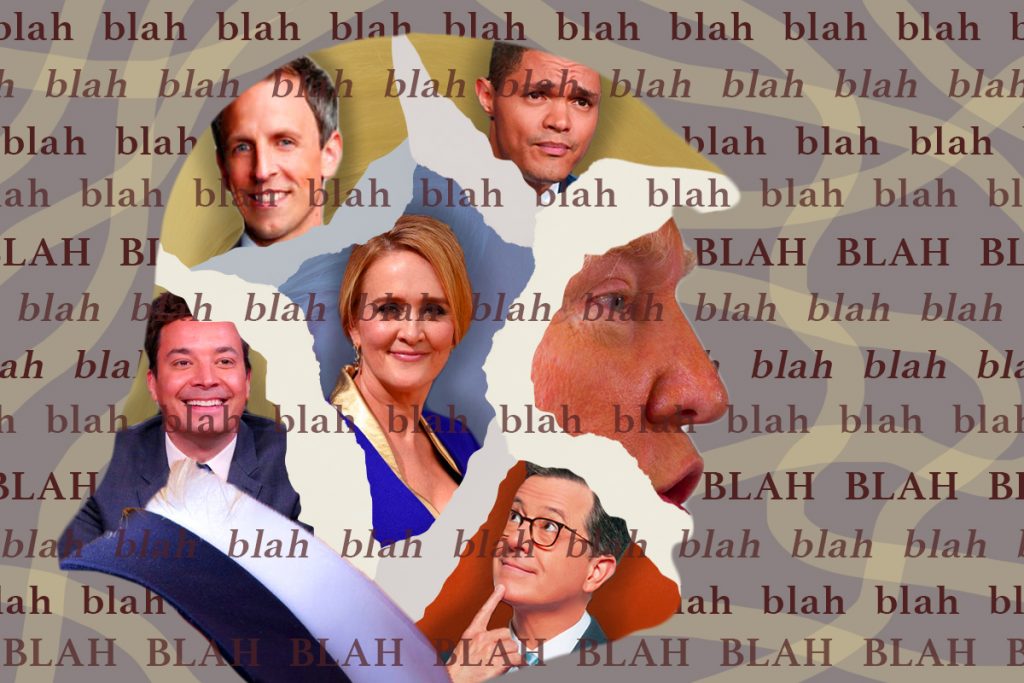

In the late-night shows’ comical and, at times, noble criticism of President Donald Trump, here are some of the recurring themes and explanations of just why Trump is terrible:

- His poor grasp of economy.

- His long tie.

- His pathological lying tendency.

- His hair.

- His sexual harassment history.

- His diet.

- His constant abuse of power.

- His word mispronunciation, his hands, his skin, his gait, his face, his way of drinking water, and so on.

How can one make an articulate case against the graceless attacks of the President and his right-wing media apparatus on others’ genders and appearances, when the next moment they themselves fall into ridiculing not only Trump’s, but his staff, supporters, and even party members’ appearances?

I get it. It’s late-night comedy. It’s political punditry. It’s not supposed to be taken very seriously. But in the age of Trump, late-night comedy has soared to the heights of utmost liberal purity, a funny but truth-telling voice, a steadily-illuminating beacon of light in the chaotic darkness. But late-night shows aren’t just attacking Trump’s characters and his harmful policies, they’re belittling and humiliating everything about him.

One might say Trump has it coming. After all, his favorite thing to do as President is to hold rallies and scream out into the night incitements of violence, hatred, and bigotry. But does it really justify the hypocrisy of these ultra-liberal mouthpieces? Is it right to do unto Trump what he does unto others?

By belittling even harmless quirks of Trump and his followers, late-night shows go against the very inclusivity that their liberalism so proudly tout. Yes, Trump might be an objectively unattractive man who shames women’s appearances, but if the reaction to that is righteous indignation, why must it always be coupled with dehumanizing mockery?

Tongue-lashing might get comedians some cheap, quick laughs, but it’s often more harm than good. An instance of this is Samantha Bee, who, after calling Ivanka Trump a “feckless c***,” had to issue an apology, along with her network, TBS. Another instance, credited also to Bee, was when her show had to apologize to a young Republican man for saying he had “Nazi hair,”— a look that in reality resulted from stage-four brain cancer.

Comedian Trevor Noah, who hosts “The Daily Show” and who builds his show’s identity around his South African experience, was more than eager to eviscerate Trump and Republican politicians during the 2016 elections. A few weeks after Trump was elected, however, he wrote an Opinion piece for the “New York Times” titled “Let’s Not Be Divided. Divided People Are Easier to Rule.” A mere month later, he went back to bashing Trump’s hair, tie, obesity, hands, face — jokes that cheapen not only his perspective, but his sincerity.

By stripping an entire group of people of their dignity and consideration for their intellectual ability, late-night shows undermine their own ideological validity and, as a consequence, widen the divide between the progressives and the conservatives. One might question how they can do it while, with equal vehemence, lament the fact that America is divided. An “Atlantic” article put this best: “When Republicans see these harsh jokes, […] they see exactly what Donald Trump has taught them: that the entire media landscape loathes them, their values, their family, and their religion.”

In a way, these shows project the voice of a frustrated people. The resistance, some might say. No healthy democracy is complete without it. But how healthy can that democracy be, really, when even within one single expression of that resistance is a self-contradiction? What do you call the railing against the cruel and the graceless through cruel and graceless means? Is it still rationalized criticism?

Or capitalism?

Or tribalistic rage?