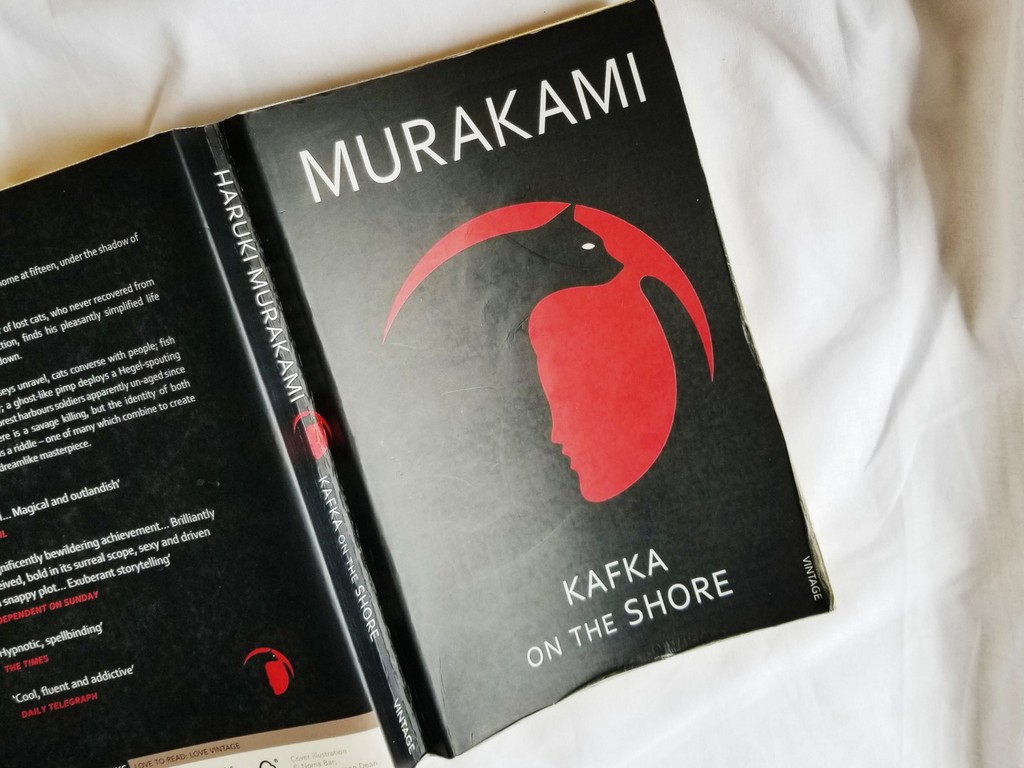

Stuff you should read: ‘Kafka on the Shore’ by Haruki Murakami

“Kafka on the Shore” follows a teenage boy, Kafka Tamura, as he leaves home in an attempt to escape an oedipal prophecy imposed by his father while searching for clues of his mother and sister. Among the remarkable cast of characters, there’s also an old man named Nakata, who suffered a freak accident as a child and lost his conventional intelligence but gained the ability to talk to cats.

Kafka and Nakata appear to be living parallel lives despite their great differences, and although each character goes on a separate quest, their paths find unexpected ways to converge. Their journeys are rich with events that escape all logic and reason, creating a surrealist and almost psychedelic reading experience, where readers discover just as much of themselves as they do of the characters.

“Kafka on the Shore” isn’t the kind of novel that can be over-analyzed as a classic in an English class. There are no right or wrong answers when it comes to finding the author’s intentions, and attempting to do so extensively will only take a lot away from the rewarding reading experience. Although Murakami’s language is accessible, precise and stimulating for the imagination, he never explains what is going on — at least not explicitly. Most of the hard work must be done by the reader, who gets to decide what the novel is supposed to do or say. It could be a study of love and memory for some, a coming of age story, an exploration of life and death and other dimensions … or anything else. There are no limitations to what this novel can offer.

It’s possible that you will be left with more questions than answers by the end of this book, but what you will have is the certainty that you’ve experienced a rush of feelings so complex and vast that few other novels have given you before. “Kafka on the Shore” is meant to be felt, not dissected. One must agree to follow Murakami with an open mind, letting his descriptions and his strangeness wash over you.

But inside the apparent chaos, there are also beautiful revelations about philosophy, art, literature, war and violence. Murakami’s writing was greatly influenced by classical music, and one of his characters, Oshima, explains to Kafka just how powerful such music can be. The title of the novel itself is also tied to music, but I can’t explain how to someone who hasn’t read the novel and spent nights wondering about its secrets.

There are specific scenes of the novel that have stuck with me even months after finishing it. Scenes that are cryptic but simple, beautiful in their description and at the same time sad, because they only live in the unreachable past. I remember fish falling from the sky. A flute made of cat souls. A troubled ghost obsessed over a painting.

I know I must return to the novel eventually and read it with a different mindset, more for the enjoyment of the words and not exactly the meaning. That I will figure out afterward. Or perhaps never. And that is OK.

What’s not OK is denying yourself the chance to read Murakami.

“And once the storm is over, you won’t remember how you made it through, how you managed to survive. You won’t even be sure, whether the storm is really over. But one thing is certain. When you come out of the storm, you won’t be the same person who walked in. That’s what this storm’s all about.”