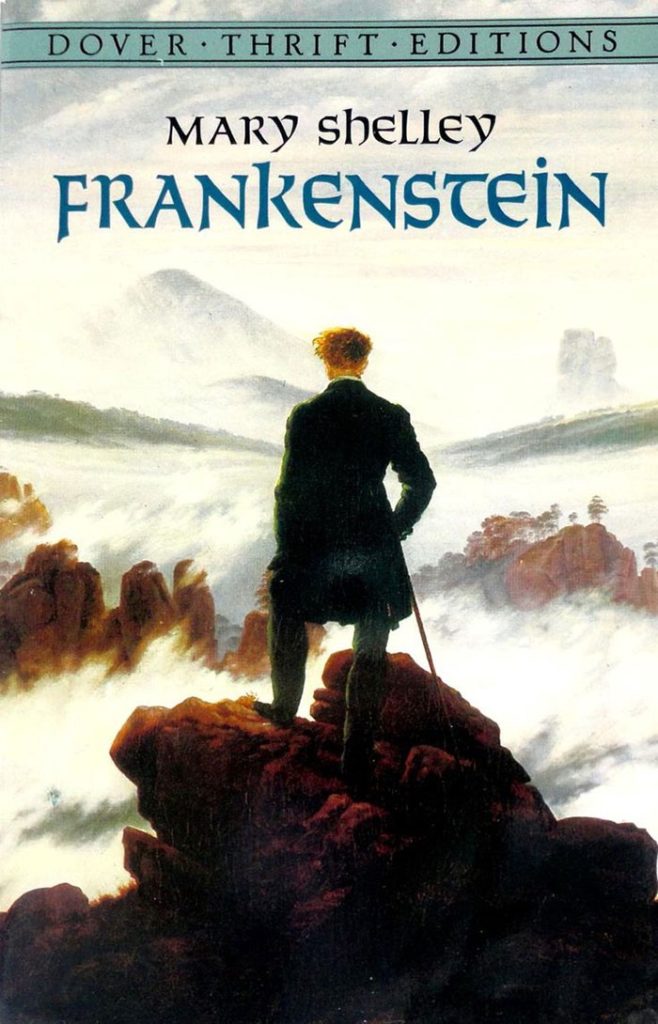

Stuff you should read: ‘Frankenstein’

Everybody has some vague idea of who Frankenstein is. The name has been embedded in pop culture for decades and served as inspiration for artists and consumer culture alike, but the source material deserves as much attention as the iconic characterization of Frankenstein’s “monster.”

Although monster might not be the best word to describe the creature. Mary Shelley’s novel invites us to question what makes a monster, whether we find one within ourselves or discover it as a consequence of our actions, making that relationship not only interesting to read about but also relevant today. Arguably the first science fiction novel of all time (with a touch of gothic horror) “Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus” is the warning sign that still resonates in a technology-driven era. Just because science and technology allow us to do something, does that mean that we should? It depends. Shelley showed us the dangers of playing God and stepping into the unknown because of our own arrogance and ambition. This idea has inspired filmmakers and authors since the book’s publication, as seen in “Westworld,” “Her,” “Ex-Machina” and “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” (aka “Blade Runner.”)

Mary Shelley was the most badass teenager of the 19th century. At the age of 18, she wrote “Frankenstein” in three days after her friend Lord Byron suggested an improvised contest to his intellectual friends: each person had to write a ghost story.

Modern readers might be discouraged to tackle a classic due to its language and story structure but it’s worth the try with a novel like “Frankenstein.” First of all, it’s not even that dense compared to other classics. Sure, the story has a slow beginning, but understand that at the time it was written, that was the standard norm that most authors followed. Everything was slow back in the day. Don’t expect the creature to start its rampage on page two. There is a setup, a mystery that creeps in and creates the gothic environment, so it demands a change of mindset from the reader in order to be appreciated. It’s worth the attempt.

Shelley’s narrative becomes interesting when Victor Frankenstein descends from hero to monster. The word “villain” isn’t so appropriate here, but monster is, as it is widely discussed. It’s impossible not to sympathize with the Creature once we get to read about its difficult journey, its loneliness and rejection from society which cause him intense pain and anger. We’re almost driven to resent Frankenstein. However, the Creature does commit crimes and develop intelligence, so the reader is entitled to judge its actions just as much as it judges its creator. The moral dilemma has different layers and no definitive answer. Additionally, it invites us to take a hard and long look at ourselves and find the similarities we might share with both Victor and the Creature.

Their story addresses fatherly abandonment and the moral consequences that come with it. What would have become of the Creature if Victor had loved it instead of abandoning it and hating it? The Creature was as intelligent as any other person and perfectly capable of expressing emotions.

Revenge takes over a long portion of the narrative. It becomes a cycle, an obsession, and in the end it drives both characters to their end. Revenge consumes them. There’s a lesson in that. Victor, despite all his fault, was a brilliant scientist and an intellectual whose life ended in complete suffering. He was also a man full of possibility but his sad emotions (anger, arrogance, ambition) overwhelmed him just as it happened to the Creature. Their relationship can also represent what happens when we run away from our problems and let them grow to the point where they chase us forever and weigh us down to a point of complete regret and emotional anguish. This concept applies to any problem, not just a scientific experiment gone wrong. But Shelley’s incarnation of the problem as a monstrous creature makes the concept more powerful, closer and therefore terrifying. We don’t see the Creature that often in the novel, just like we don’t see problems up close but we know they’re still present, maybe far away but never gone. Until one day, they come knocking at our door and we can’t afford the luxury of ignoring them.