Art auction 101: A crash course in art, business and big money

Have you ever wondered how the art market works? The art market has always been a mystery to people who aren’t business-savvy, like me. I never had the motivation to learn more about it. I finally decided to do more research about the art market, particularly art auctions, after working at a recent Hong Kong art auction this week. If you’re interested in art auctions and how they operate, keep reading. I will be covering questions such as if artists receive any money from auctions and why artworks could be sold at sky-high prices.

What is an art auction?

Art auctions are the so-called secondary market for artists to sell their artworks. Galleries are the primary market to sell work to private collectors or institutions where there are direct transactions between artists, galleries and the buyers. In the secondary market, works are sold through auction houses.

In an art auction, people bid against each other to purchase an artwork. Auction prices can range from $2,000 to $200 million. The most expensive painting ever sold in an auction was Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘Salvator Mundi’, which sold for a record $450 million last November.

What kind of artists get to sell their pieces in auctions?

Not every artist can sell their paintings in auction houses. Those who do need to have a list of successful gallery or museum exhibitions, and have the traction of fame to make it to the secondary market.

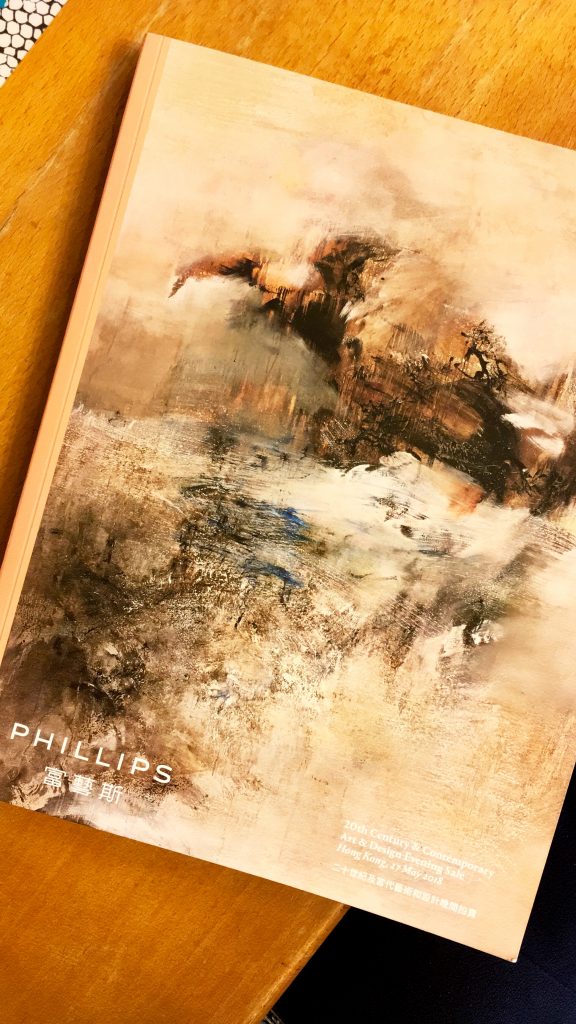

What are some of the notable auction houses?

Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Philips are some. And there are also online art auction websites such as Artnet.com.

Where do the works come from? Where do auction houses find the works?

Works usually come from consignment. A person — often an art dealer or collector — lends a piece to an agent who will help initiate the sale by finding potential buyers or by putting up an auction. In simpler terms, art dealers and collectors (the consignors/borrower) approach auction houses (the consignee/seller) and ask them to sell pieces they have. Consignors pay a commission price to the auction house depending how much the work is sold for. The auction house benefits from selling expensive art because they earn more.

Before consignment, auction houses evaluate the pieces and see if they are worthy of an auction. Sometimes they decide that the works would sell better through private sales in the primary market. The process of assessing the artwork’s market value is called appraisal.

Will auction houses actively seek artworks to sell?

They do, but not aggressively. Like a game of fishing, auction houses focus on building relationships with collectors. Their specialists wait for a good time to advise their clients to sell their works or sometimes buy a work, depending on factors like market trends or artist fame and publicity.

There are also cases where collectors announce their intention to sell a collection or a piece and auction houses create consignment proposals, arguing why they should be the auction house to sell the work. In a case that took an unexpected turn, Japanese electronics manufacturer Maspro Denkoh decided in 2004 to sell its corporate collection of Impressionist paintings — including works by Cezanne and Van Gogh. The two big-name auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s, submitted proposals for the consignment. Takashi Hashiyama, the company’s president, couldn’t decide between the two, so he proposed a game of rock, paper and scissors between Sotheby’s and Christie. The winner would take over the collection and sell them. Christie ended up winning the game and they gained $1.9 million in commission when they sold the collection for $17.8 million in May 2005.

Who can join the auction?

The auction is open for everyone to view and participate, usually taking place in a convention hall or hotel. Bidders register for a paddle before the auction. A paddle looks like a ping-pong paddle and it’s something the bidder raises during an auction to make a bid. Some paddles are used to telegraph the amount of bids placed by the client. There are pricier artworks called premium lots that require interested bidders to make a deposit in order for the auction house to have some financial references. For example, Phillips’ recent Hong Kong spring art auction require clients to make a deposit of $255,000 or more for premium lots.

Will the artists be involved or get a slice of the money?

It depends on who the consignor is. When artists work with consignors, they get paid as both parties would split the bidding. There are also cases when the artist doesn’t get a penny. That’s when the consignors are collectors, galleries or art dealers who already purchased and own the artworks. As they consign the works with full property ownership, they get to keep all the bidding as the work sells. The artists don’t get paid unless the consignor decides to split the “trophy,” but that is not a common practice within the auction industry.

What are some of the reasons people buy art?

Some people buy art as an investment. For example, a collector could lock down an emerging artist and buy one of their works. As the artist’s fame rises, the collector could consign the painting to auction houses and sell it at a much higher price. However, if the artist suffers from scandals, the collector would not be able to sell the artwork with a profitable price because the artist and their works would be deemed much less desirable. Art values can be unstable in the market and affected by many uncontrollable factors.

Another theory for buying works is for tax cuts. In the United States, donating artworks to institutions can be counted as an act of charity. It’s not unheard of for people who buy expensive paintings and donate them to museums. They get tax cuts for the donation that are worth even more than the painting’s purchase price. It’s possible to make a profit by buying and donating artworks.

Then there are also always people who buy art pieces in auctions because of passion for the arts or artists. In 2013, a Francis Bacon triptych, “Three Studies of Lucien Freud,” was sold in Christie’s fall auction. The triptych was initially separated because each panel was purchased individually. For years it was divided among collectors, but with a lot of effort, a specialist from Christie’s was able to have the panels reunited. An article from Esquire UK mentioned this story explained what happened. A 26-year-old book dealer fell in love with the triptych after seeing a copy of it in a catalog. In the auction, he went after the painting for $85 million as his first bid and then $125 million as his second. At the end, he, unfortunately, was outbid and the painting was sold for $142 million to someone else. But this shows how, given they have the financial ability to afford it, people are willing to pay a huge amount of money for something they genuinely appreciate.

What determines the set price?

The prices for the works are determined by the works’ provenance and exhibition history. Provenance means the chain of ownership of the work ever since the artwork had been created. It can significantly enhance the value of a work, especially if one or more of the owners are prominent collectors, such as the Rockefellers.

A work’s exhibition history can also pump up its price, as being featured in successful galleries and museum shows would make a work seem much more desirable. French artist Jean Dubuffet’s “Le Chien Rôdeur” was sold for $961,000 in Phillips’ Hong Kong spring art auction. The piece has been shown in The Art Institute of Chicago, Tate Gallery in London and the Guggenheim in New York.

The price is also determined by who the artists are, their historical significance, influences in art history and at what point the artwork was produced in the trajectory of an artist’s career. Dubuffet’s “Le Chien Rôdeur” depicted a dog in a semi-representational form that is different from his more abstract paintings. On the other hand, it also showed Debuffet’s earlier interest in earth and soil that is so prominent in his later works. Works that document a change in the artistic process cost much more than works that are more common to the artist’s other works.

Art auctions are complicated, and it’s easy to be overwhelmed by all the business jargon and sheer intensity of them. Luckily there’s always information from websites, blogs, podcasts, books and films. Auctions are also open and free of charge for anyone to attend, so if you want to experience what it’s like being in an auction, see drama unfold and watch rich people spend big money, search up any auctions near your area and show up in a fancy dress or suit.